SpermSearch: AI-powered tool can help treat male infertility 1000x faster than embryologists

SpermSearch can highlight potentially viable sperm before doctors can even process what they're looking at, says researcher

In a new breakthrough, an artificial intelligence (AI) powered tool, SpermSearch, has proven to be a powerful tool to help treat male infertility, a medical problem that affects 7% of the male population worldwide.

According to Dr Steven Vasilescu, the AI programme — SpermSearch — he and his colleagues built can identify sperm in samples from extremely infertile men 1,000 times faster than a pair of highly trained eyes.

"SpermSearch can highlight a potentially viable sperm before a human can even process what they're looking at," he says.

Dr Vasilescu is the creator of the medical firm NeoGenix Biosciences and a biomedical engineer at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) in Australia.

SpermSearch is the name of the system he and his colleagues have created, BBC reported.

It has been created to assist men who, like 10% of infertile men, have absolutely no sperm in their ejaculate, a condition known as non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA).

Typically, a little bit of the testes is surgically removed in these situations, and it is then transported to a lab so that an embryologist may manually look for viable sperm.

The tissue is dissected and then looked at under a microscope. It is possible to harvest and inject viable sperm into an egg if any are discovered.

According to Dr Vasilescu, this process can take many employees six or seven hours, and there is a risk of exhaustion and accuracy.

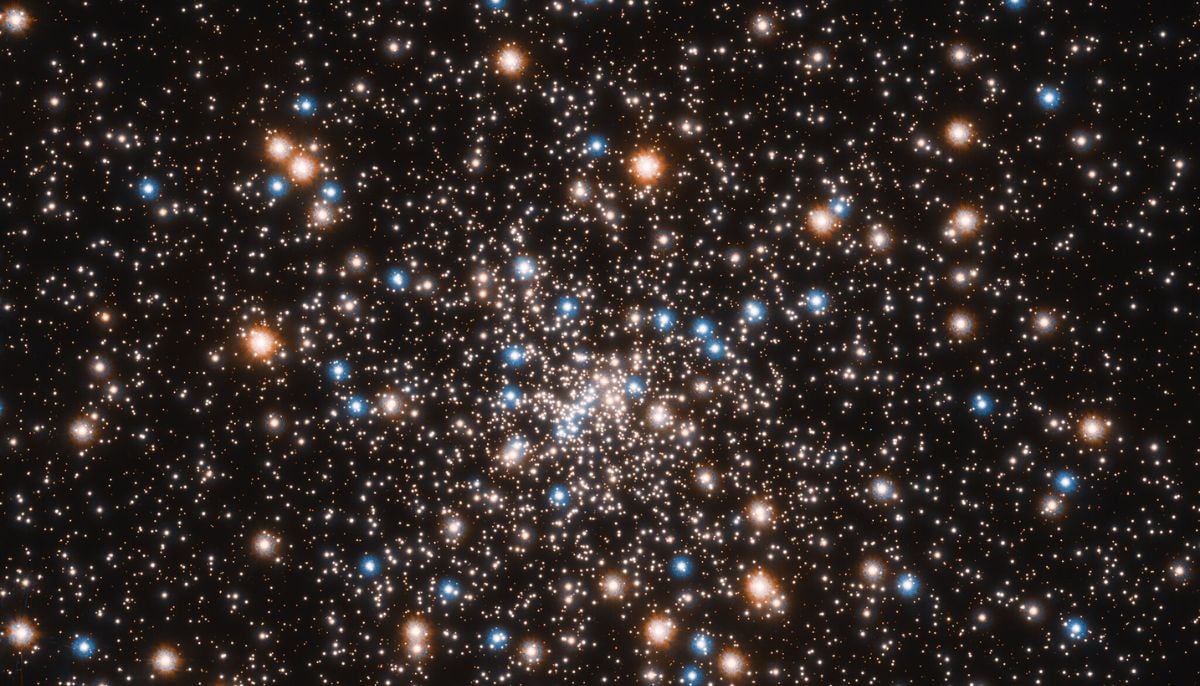

"When an embryologist looks down the microscope, what they see is just this complete mess - a starscape of cells," he says.

"There's blood and tissue. There might be only 10 sperm in the whole thing, but there can be millions of other cells. It's a needle in a haystack," says Dr Vasilescu.

Contrarily, he claims that SpermSearch can quickly locate any healthy sperm when photos of the samples are promptly uploaded to the computer.

Dr Vasilescu and his associates taught the AI to recognise sperm in these intricate tissue samples by exposing it to hundreds of similar photos in order to reach this speed.

The UTS biomedical engineering team reported that in a test SpermSearch was 1,000 times quicker than an expert embryologist in a published scientific study.

SpermSearch is a useful tool, but it is not intended to take the role of embryologists.

Dr Sarah Martins da Silva says that such speed in finding any sperm is vital. "Time is critical," says the clinical reader in reproductive medicine at the University of Dundee.

"If you've got somebody that's had an egg collection, and you've got eggs that need to be fertilised, there's only a small time window for us to be able to do that. Speeding up the process would be hugely advantageous."

Infertility is still a rising issue, with sperm levels commonly thought to have decreased by 50% over the previous forty years.

According to reports, there are a variety of factors contributing to the decline in male fertility, from smoking and pollution to bad diets, insufficient exercise, and excessive stress.

-

Total Lunar eclipse: What you need to know and where to watch

-

Sun appears spotless for first time in four years, scientists report

-

SpaceX launches another batch of satellites from Cape Canaveral during late-night mission on Saturday

-

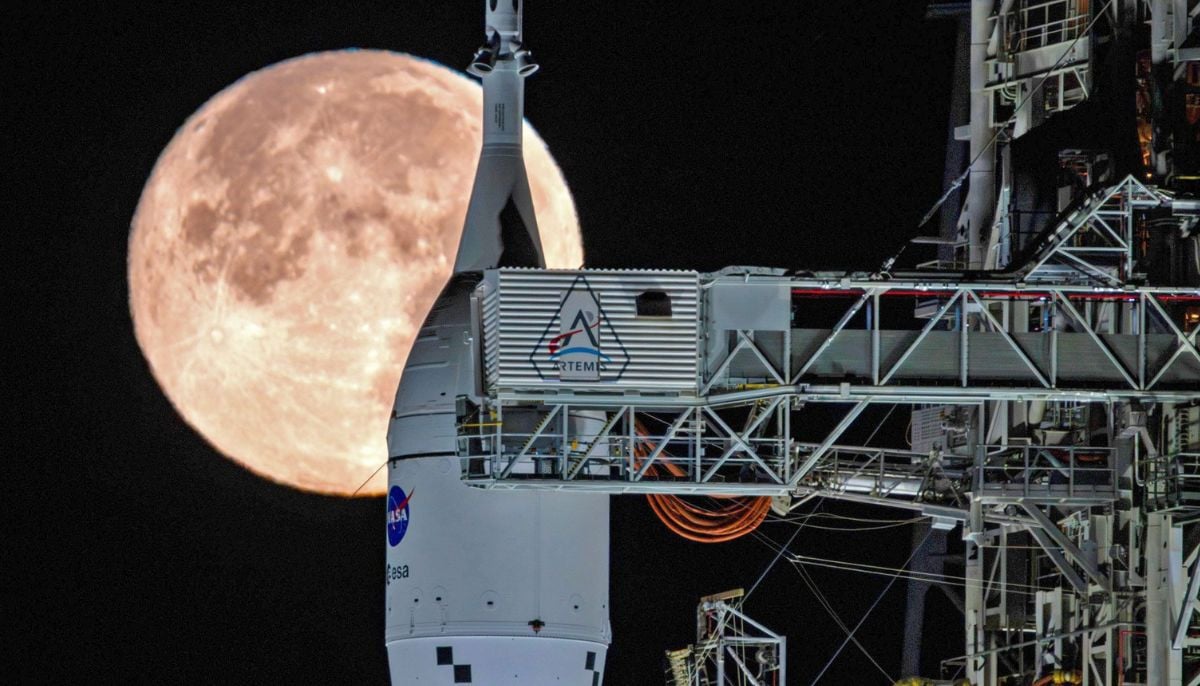

NASA targets March 6 for launch of crewed mission around moon following successful rocket fueling test

-

Greenland ice sheet acts like ‘churning molten rock,’ scientists find

-

Space-based solar power could push the world beyond net zero: Here’s how

-

Hidden ‘dark galaxy' traced by ancient star clusters could rewrite the cosmic galaxy count

-

Astronauts face life threatening risk on Boeing Starliner, NASA says