Why did Mark Zuckerberg cover his kids’ faces on Instagram? Here's what we know

Meta CEO's recent Instagram post sparks concerns about the social media platform's privacy

Mark Zuckerberg recently posted a family photo on Instagram celebrating the Fourth of July, and netizens were quick to notice two things: the billionaire CEO wore a striped souvenir cowboy hat and the emojis covering his children's faces.

Some people immediately criticised Zuckerberg's post because they believed that his choice to mask the faces was a reflection of his privacy concerns for posting pictures of his children online, despite the fact that he has built enormous platforms that permit millions of other parents to do the same.

Instagram's parent company, Meta, has long faced criticism for how it manages user privacy as well as for how its algorithms can be used to steer young users down potentially dangerous rabbit holes.

The decision, however, also draws attention to a wider trend among some social media users, particularly among well-known people, to be more circumspect when sharing identifiable images of their children online.

Several celebrities have been blurring pictures or using emojis to help protect their children's privacy on social media for years. In the past, Zuckerberg had also posted images of his daughters' side profiles and backs rather than their full faces.

Ordinary users do not often adopt a similar strategy, but perhaps they should.

"By modelling for us that he was careful not to share his family’s location or children's identities, he may be communicating that it is the end users' responsibility to protect themselves online,” said Alexandra Hamlet, a New York City-based psychologist who closely follows the impact of social media on young users.

Meta did not respond to a request for comment.

Parents and experts are increasingly concerned about sharing embarrassing pictures of their children on social media, as it may expose them to identity theft and facial recognition technology, CNN reported.

This could create an internet history that can follow them into adulthood. Some parents limit sharing, limit sharing to less public platforms, or use clever hacks like obscuring their children's faces.

Leah Plunkett, author of “Sharenthood” and associate dean of learning experience and innovation (LXI) at Harvard Law School, said blocking a child’s face is a symbol that you’re giving them control over their own narrative.

"Every time you post about your kids, you are chipping away at allowing them to tell their own stories about who they are and who they want to become," she said.

"We grow up making mischief and more than a few mistakes and grow up better having made them. If we lose the privacy of teens and kids to play and explore, and to live and through trial and error, we will deprive them of the ability to develop and tell stories [on their own terms]," she added.

Furthermore, Zuckerberg did not choose to obscure the face of his infant child, which may indicate less concern for the baby's face risks, but Plunkett suggested that artificial intelligence technology can trace face changes over time, potentially connecting older children to childhood images.

She hopes that social media companies can offer settings to automatically blur kids' faces or prevent child-related images from being used for marketing or advertising.

Nonetheless, for the time being, it is up to the parents to restrict or forgo internet sharing of their children's images.

"It's not just parents – grandparents, coaches, teachers, and other trusted adults should also keep kids out of photos and videos to protect their privacy, safety, future and current opportunities, and their ability to figure out their own story about themselves and for themselves," she said.

-

Total Lunar eclipse: What you need to know and where to watch

-

Sun appears spotless for first time in four years, scientists report

-

SpaceX launches another batch of satellites from Cape Canaveral during late-night mission on Saturday

-

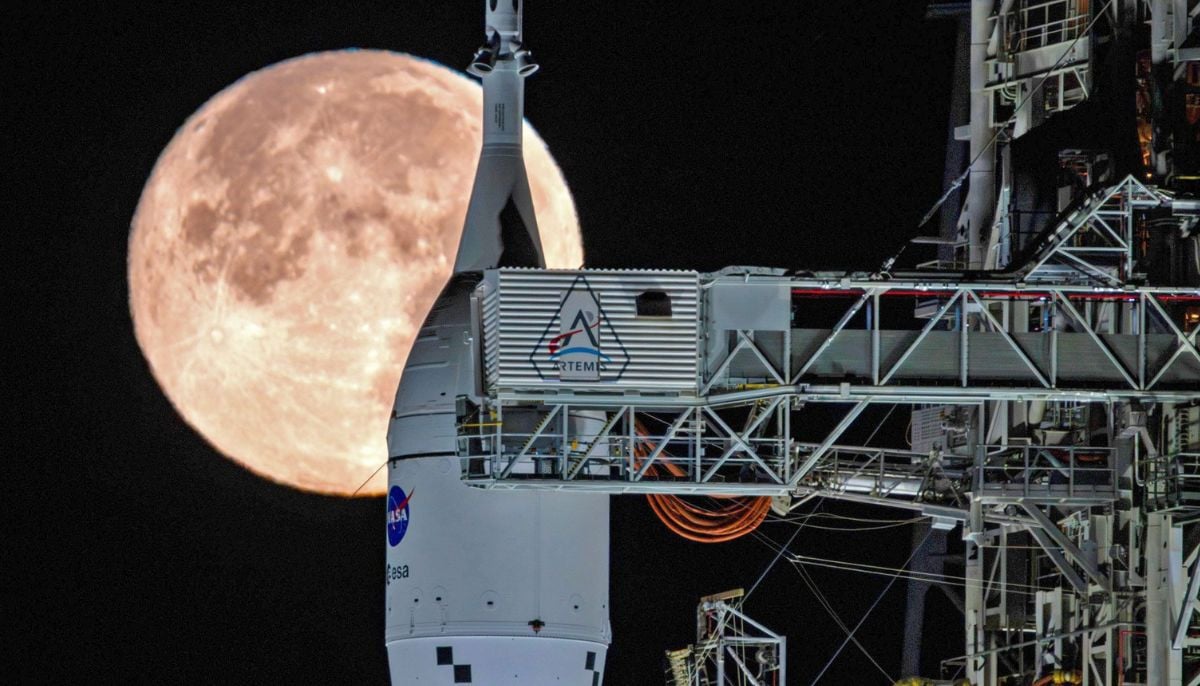

NASA targets March 6 for launch of crewed mission around moon following successful rocket fueling test

-

Greenland ice sheet acts like ‘churning molten rock,’ scientists find

-

Space-based solar power could push the world beyond net zero: Here’s how

-

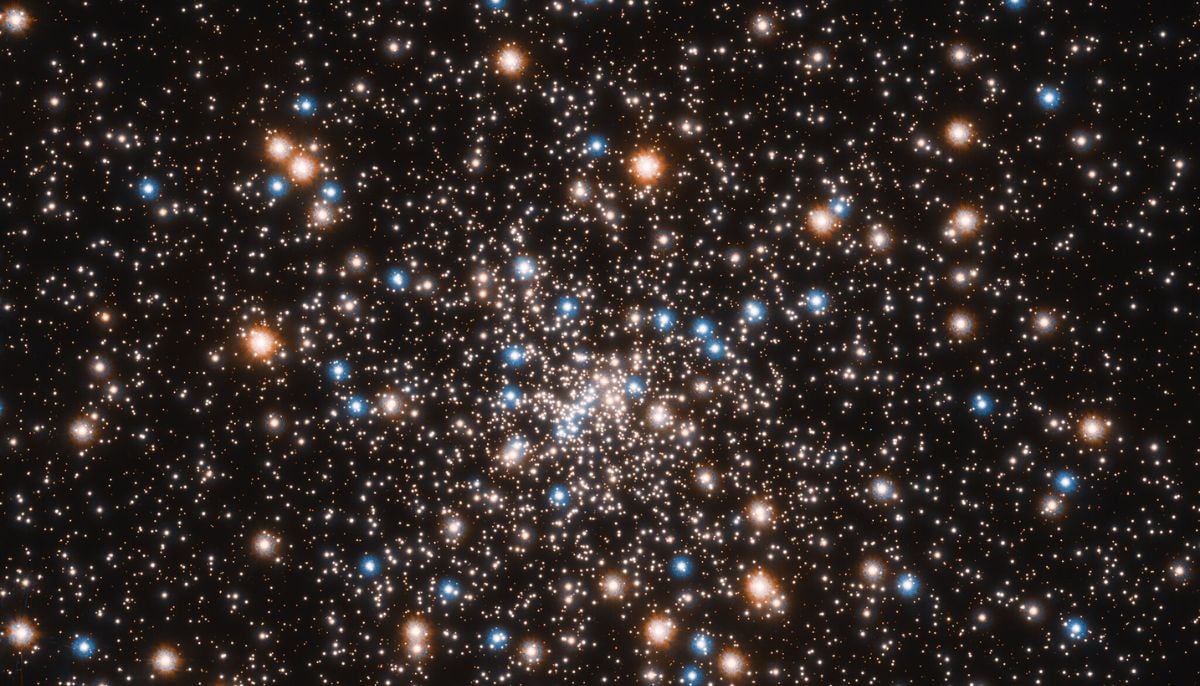

Hidden ‘dark galaxy' traced by ancient star clusters could rewrite the cosmic galaxy count

-

Astronauts face life threatening risk on Boeing Starliner, NASA says