Obesity alters brain’s ability to know when to stop eating: Is it reversible?

The impact on the brain may not be as easily reversed as desired, which may explain why some people successfully lose weight only to gain it all back few years later

The satisfaction that one receives from eating is inevitable, but one must remember when to stop because a new study revealed that obesity may impair the brain's capacity to recognise fullness and experience satiety after consuming fats and sugars.

Such brain alterations persist even after medically obese individuals lose weight, potentially explaining why people frequently gain back the weight they lose.

"There was no sign of reversibility — the brains of people with obesity continued to lack the chemical responses that tell the body, 'OK, you ate enough,'" said Dr Caroline Apovian, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Centre for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

According to the BBC, medically obese people possess a BMI above 30, while normal weight ranges from 18 to 25.

"This study captures why obesity is a disease — there are actual changes to the brain," said Apovian, who was not involved in the study.

Dr I Sadaf Farooqi at the University of Cambridge praised the meticulous and thorough study, adding to earlier studies on the effects of obesity on the brain, saying that it strengthens the conclusions that link obesity to these changes.

The study explained

The study, published Monday in Nature Metabolism, involved a controlled clinical trial involving 30 obese and 30 normal-weight individuals to examine the gut-brain connection to nutrients.

Participants were fed sugar carbohydrates (glucose), fats (lipids), or water as a control. The study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) to capture the brain's response over 30 minutes.

The researchers focused on the striatum — the part of the brain involved in the motivation to eat food — which plays a role in emotion and habit formation.

In people with normal weight, brain signals in the striatum slowed when sugars or fats were introduced into the digestive system, indicating that the brain recognised that the body had been fed. However, levels of dopamine rose in those at normal weight, signalling that reward centres were also activated.

"This overall reduction in brain activity makes sense because once food is in your stomach, you don’t need to go and get more food," lead study author Dr Mireille Serlie, professor of endocrinology at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, explained.

Variations in results for the medically-obese

A study found that when nutrients were given via feeding tube to medically obese individuals, brain activity did not slow and dopamine levels did not rise, especially when the food contained lipids or fats.

This finding is interesting because the higher fat content is more rewarding.

The study also asked people with obesity to lose 10% of their body weight within three months, but the brain did not reset.

This finding may explain why people lose weight successfully and then regain all the weight a few years later, as the impact on the brain may not be as reversible as desired, the BBC reported.

Room for research still remains

The study of weight gain and brain changes is complex due to the genetic component of obesity. Genetic factors, such as fat tissue, food types, and environmental factors, may influence the brain's response to certain nutrients.

Further research is needed to understand the brain's response to obesity and whether it is triggered by fat tissue, food types, or environmental factors.

Dr Serlie also emphasised that weight stigma should not be used to combat obesity, as it is simplistic and untrue.

It is crucial for those struggling with obesity to understand that a malfunctioning brain may be the reason they struggle with food intake, and this information can increase empathy for the struggle, she said.

-

Late James Van Der Beek inspires bowel cancer awareness post death

-

Bella Hadid talks about suffering from Lyme disease

-

Gwyneth Paltrow discusses ‘bizarre’ ways of dealing with chronic illness

-

Halsey explains ‘bittersweet’ endometriosis diagnosis

-

NHS warning to staff on ‘discouraging first cousin marriage’: Is it medically justified?

-

Ariana Grande opens up about ‘dark’ PTSD experience

-

Dakota Johnson reveals smoking habits, the leading cause of lung cancer

-

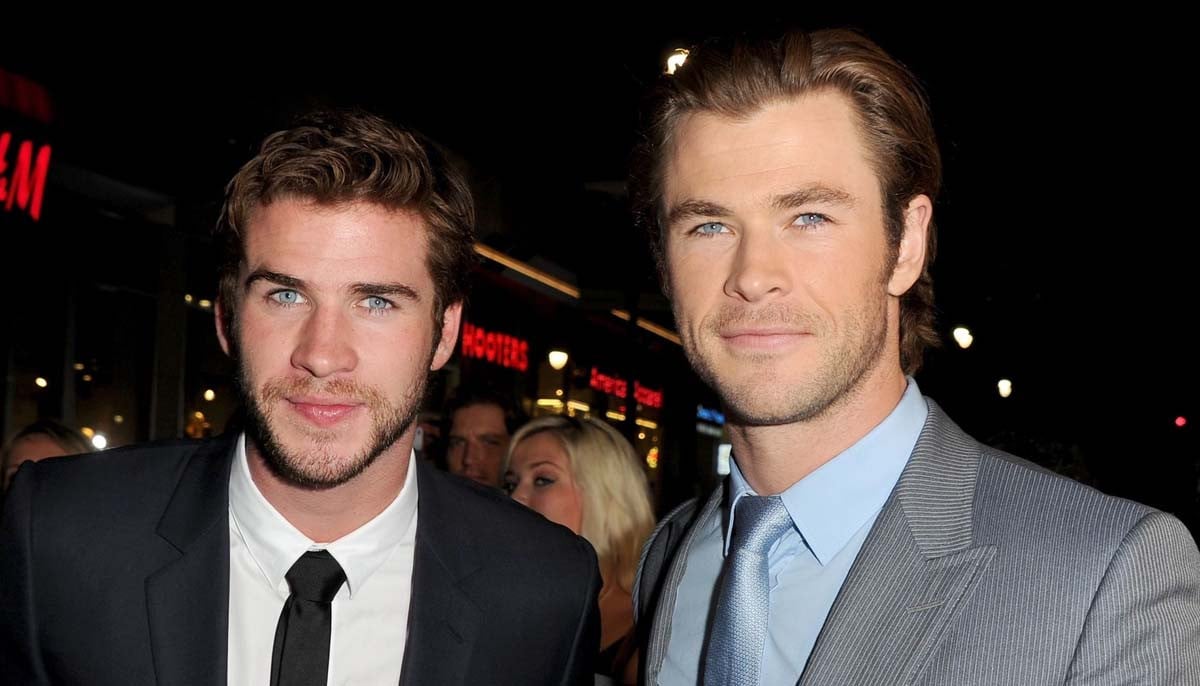

Chris, Liam Hemsworth support their father post Alzheimer’s diagnosis