New blood test can explain miscarriages and lead to preventative treatments, says study

Study was conducted by Danish gynaecologist Henriette Svarre Nielsen and her team of researchers, and was published in the British journal The Lancet

Danish researchers have found that taking a blood test after a miscarriage, as early as week five of pregnancy, can help explain why it occurred and even lead to preventative treatments.

The study, called COPL, is ongoing, and all women who have suffered a miscarriage and visited the Hvidovre hospital emergency room are offered the blood test to determine if the foetus had a chromosome anomaly.

The project aims to develop treatments, provide support, and gather data to answer questions properly about pregnancy loss and women’s health in general.

Miscarriage affects one in 10 women, with rates even higher in countries where pregnancies occur later in a woman’s childbearing years. The blood test can determine whether the foetus had a chromosome anomaly, which is the case in 50 to 60 percent of miscarriages. If anomalies are found, doctors can determine the risks of future miscarriages and devise a treatment plan. Even if no anomalies are found, doctors can start a search for answers to determine the cause of the miscarriage.

The study was conducted by Danish gynaecologist Henriette Svarre Nielsen and her team of researchers, and was published in the British journal The Lancet. Svarre Nielsen notes that such tests are usually only offered after a woman has suffered three miscarriages in Denmark, and only if they occurred after the tenth pregnancy week. She hopes to change this practice, stating that “this is 2023. We are way beyond just counting as the criteria” to investigate why somebody may be prone to pregnancy loss.

As part of an ongoing study at Hvidovre hospital near Copenhagen, all women who have suffered a miscarriage and visited the emergency room are offered the blood test. Over 75 percent of them have accepted so far. The project, known as COPL for Copenhagen Pregnancy Loss, was launched in 2020 and is still underway, with a cohort of 1,700 women so far. Svarre Nielsen hopes that this project will yield a unique database on a wide range of illnesses related to pregnancy loss, reproduction, and women’s health in general.

Svarre Nielsen, who has over 20 years’ experience in reproductive health, is keen to develop treatments for pregnancy loss. She notes that pregnancy loss is very common, with 25 percent of all pregnancies ending in a pregnancy loss. However, there has been little focus on finding explanations or supporting the mental health of couples after a miscarriage. Rikke Hemmingsen, who suffered three miscarriages before giving birth to two children, notes that she wishes the project had been around to help her. She hopes that the findings of the study will help prevent others from going through the same thing.

Pregnancy loss is often not discussed publicly, and when it is, reactions can be awkward. Hemmingsen notes that “everyone saying ‘this is normal’ doesn’t make it more normal, or more or less sad to the one it happens to.” The taboo can also make it harder for couples to get proper treatment. Hemmingsen calls for more openness about pregnancy loss and for specialists who can help couples who suffer miscarriages.

Overall, the study’s findings could ultimately help prevent five percent of the 30 million miscarriages seen worldwide annually. By identifying the cause of miscarriages and developing treatments, Svarre Nielsen hopes to make the grief and sadness of every pregnancy loss matter and to help fewer women have to go through the same thing.

-

Late James Van Der Beek inspires bowel cancer awareness post death

-

Bella Hadid talks about suffering from Lyme disease

-

Gwyneth Paltrow discusses ‘bizarre’ ways of dealing with chronic illness

-

Halsey explains ‘bittersweet’ endometriosis diagnosis

-

NHS warning to staff on ‘discouraging first cousin marriage’: Is it medically justified?

-

Ariana Grande opens up about ‘dark’ PTSD experience

-

Dakota Johnson reveals smoking habits, the leading cause of lung cancer

-

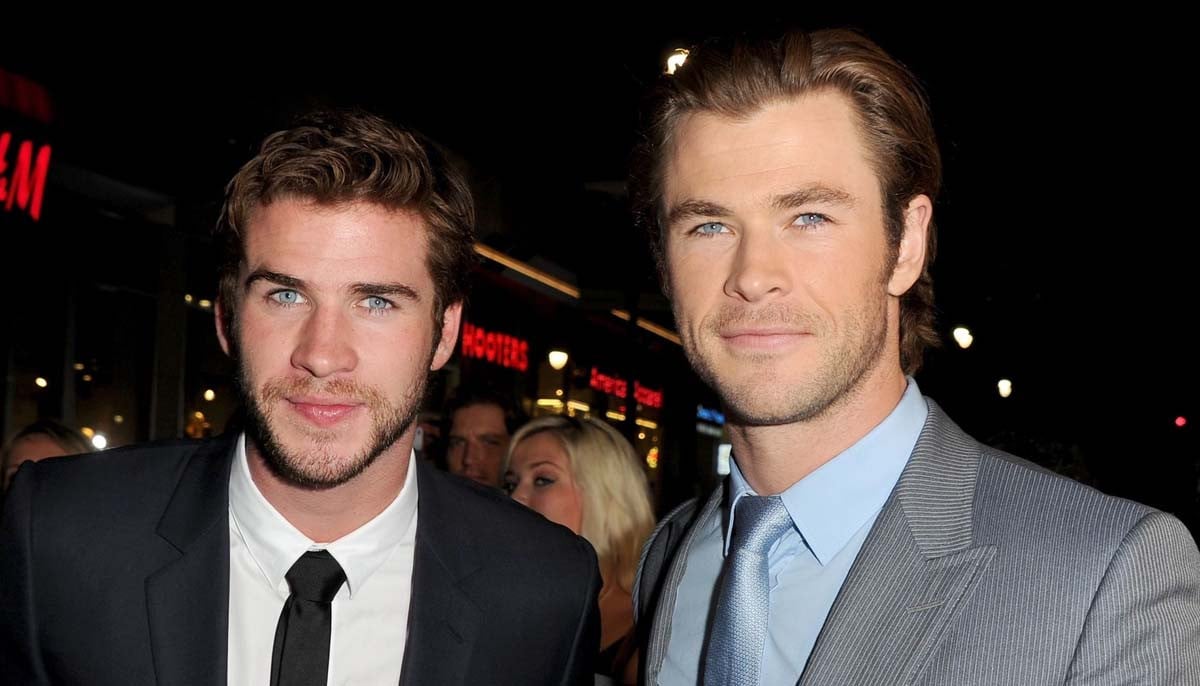

Chris, Liam Hemsworth support their father post Alzheimer’s diagnosis