Will the end of conflict mean peace?

The decade-old debate of whether the conflict in Waziristan is ‘ours’ or ‘theirs’ has intensified si

By Afiya Shehrbano

November 15, 2013

The decade-old debate of whether the conflict in Waziristan is ‘ours’ or ‘theirs’ has intensified since we elected in a new government this year. The reason for this is clear.

A conservative government that is aligned and sympathetic to religious politics necessarily wants to shift the responsibility for the Islamist insurgency in Pakistan. Hence they redefine the nature of conflict from a war on Pakistan by religious militants to one that is simply due to US occupation and a fallout of the WoT.

The new narrative converts terrorists to stakeholders and allows policy change from defence to dialogue. Certainly, there must be an end to all forms of conflict but the process of getting to peace is equally critical.

Changing the narrative is not easy and the conservatives are floundering to disguise their natural bias. Hence Imran Khan’s statement that he is not anti-America or anti-India but against their politics stops short of extending the same logic regarding the Taliban’s militancy or political agendas. In contrast, at least the Islamists are clear.

The recent burst of pent-up emotional religio-political rhetoric by the JI, qualifying the Taliban as true shaheeds against the illegitimacy of Pakistani soldiers is a significant comment on who qualifies as a good Muslim and who deserves to be stripped of that honour.

For those who have argued consistently against the false distinctions between religious extremism and routine religious politics, this is not a revelation or shock. The JI is simply articulating what many religious conservative sympathisers and so-called anti-imperialists share – their positioned hatred for the US, and/or infidels and western imperialist aggression.

At least the JI clears the academic attempts at obfuscation of religious politics that we have been subjected to for the last decade. Now, all religious actors claim to be a collective global imaginary ‘us’ against America and by extension also against us not-Muslim-enough Pakistanis.

All the ‘stakeholders’ agree that conflict must end but none discuss what is the nature of peace that will follow. For some limited and expedient politicians and analysts this will be when America exits the region. Such analysis relies on the thinking that religious militancy and conflict only exist in Waziristan. This view refuses to recognise the clear spread of physical networks and the metaphysical nexus of Shariah-imposing groups that are now embedded in all the provinces.

Those who believe in the theory of drones leading to militancy for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa ignore the fact that drones do not drive militancy in other parts of the country. Forget southern Punjab, come and visit the unlikely Karachi town of Baldia for a surprising lesson on this front or, even the peaceful city of Sahiwal in north of Punjab for that matter.

Those who insist that the WoT has caused or even intensified brazen religious oppression in educational institutions, press clubs, printing presses, the judiciary and bar associations, have never visited a jail or university in Pakistan in the last two decades. They’ve been busy watching the drones in the skies and missing the systematic success of religious piety and well-funded, organised, independent rise of religious politics on the ground – pre 9/11. They pretend that the narrative on religious extremism is simply a case of misguided ideology and lack of ‘education’.

There is also the amazing and even arrogant advice to native Pakistanis that they have not ‘engaged’ enough with religion intellectually or academically and this is the cause of misguided religious bigotry and murderous results. Such arguments emerge from the luxury of historical amnesia and long-distanced clinicians who sit in western academia oblivious of the ‘engagements’ that have marked the relationship between Islamist groups, the state and civil society in Pakistan for 60 odd years.

This is unforgivable in a generation that has open access to the Munir Commission kind of reports – as just one example. Neither have they counted the plethora of Islamic universities, courses, programmes, piety lesson groups, theocratic ‘houses’, publications, textbooks and virtual discussion groups that crowd the private and public sector, apart from the madressahs. There is no secular academic engagement anymore – just the religious kind.

The drone debate has also intensified not just because its long-time protestor Imran Khan and his party now govern the targeted province but, interestingly, primarily because of the Amnesty International report. Earlier academic reports did not have the same impact. Ironically, human rights organisations such as westoxified and imperialist Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch used to be vilified for their ‘anti-Muslim’ exposure of child labour, women’s human rights abuses, terrorist atrocities and the exploitation and abuse by the Okara military farm administration against peasants. Now, by volte face, the report on drones is selectively quoted widely as objective proof of the ‘real’ oppression in Pakistan.

The content in the recent docu-film Wounds of Waziristan has been received in Pakistan with a bit of a yawn. This is not necessarily only because of the limited framing of a conflict that Pakistanis don’t need to be educated on but because it was a bad documentary. As Akbar Zaidi points out, in its attempt to focus on the human cost of war, the ineffectiveness of this documentary is mainly because it attempts to play on the guilt of American audiences (hence the repeated equation of New Jersey to Waziristan???) without any mention of why the drones are there.

This decontextualised perspective is misleading too for an ignorant American audience, since the film gives the singular impression that this is a war between drones and all Pakhtuns and the latter are only victims of one aggressor – the USA.

What is interesting is that some ‘anti-imperialist’ defenders of this documentary that Zaidi has clearly cut to the quick would agree to criticism of other one-dimensional productions including those produced by liberal sympathisers.

Therefore, the banned play by the progressive Ajoka group, Burqavaganza, which was a clichéd and limited production around the veil, was criticised by many of the same intellectuals who demanded more nuance and depth in political content in cultural productions. Such critics (including myself) were all too ready to dismiss the false binaries and stereotypes and decontextualised portrayal of the burqa and Islamists in the play.

For all their insistence that the WoT is a product of American hegemony and Pakistan complicity of the 1980s, and that we must be aware of the context, context, context, suddenly, all that is thrown out of the window when it comes to drones. Somehow, it’s perfectly alright to suspend the effective and real agenda of the militants and pretend that the wounds of Waziristan are only inflicted by one aerial side.

Also interesting is the argument that calls for accountability of the illegality of drone warfare. Not once, in either the documentary nor in the writings of these anti-imperialists nor in Imran Khan’s rhetoric is there a demand for accountability of the Pakistani defence services. This is not connected nor discussed in the context of the fact that an operation took place in Abbottabad after which there was zero accountability or consequences.

All such efforts support the myth that there is this invisible entity that falls between the military and government that permits the WoT to continue. This makes it simple to erase Pakistan and pretend that this is an ongoing colonial war against Waziristan. Wounds of Waziristan type of narratives aid such airy false analysis.

Such limited approaches, as exemplified in the new narrative that focuses exclusively on drones and America, are unlikely to end the conflict – at the very least, they won’t lead to staying peace.

The writer is a sociologist based in Karachi. Email: afiyazia@yahoo.com

A conservative government that is aligned and sympathetic to religious politics necessarily wants to shift the responsibility for the Islamist insurgency in Pakistan. Hence they redefine the nature of conflict from a war on Pakistan by religious militants to one that is simply due to US occupation and a fallout of the WoT.

The new narrative converts terrorists to stakeholders and allows policy change from defence to dialogue. Certainly, there must be an end to all forms of conflict but the process of getting to peace is equally critical.

Changing the narrative is not easy and the conservatives are floundering to disguise their natural bias. Hence Imran Khan’s statement that he is not anti-America or anti-India but against their politics stops short of extending the same logic regarding the Taliban’s militancy or political agendas. In contrast, at least the Islamists are clear.

The recent burst of pent-up emotional religio-political rhetoric by the JI, qualifying the Taliban as true shaheeds against the illegitimacy of Pakistani soldiers is a significant comment on who qualifies as a good Muslim and who deserves to be stripped of that honour.

For those who have argued consistently against the false distinctions between religious extremism and routine religious politics, this is not a revelation or shock. The JI is simply articulating what many religious conservative sympathisers and so-called anti-imperialists share – their positioned hatred for the US, and/or infidels and western imperialist aggression.

At least the JI clears the academic attempts at obfuscation of religious politics that we have been subjected to for the last decade. Now, all religious actors claim to be a collective global imaginary ‘us’ against America and by extension also against us not-Muslim-enough Pakistanis.

All the ‘stakeholders’ agree that conflict must end but none discuss what is the nature of peace that will follow. For some limited and expedient politicians and analysts this will be when America exits the region. Such analysis relies on the thinking that religious militancy and conflict only exist in Waziristan. This view refuses to recognise the clear spread of physical networks and the metaphysical nexus of Shariah-imposing groups that are now embedded in all the provinces.

Those who believe in the theory of drones leading to militancy for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa ignore the fact that drones do not drive militancy in other parts of the country. Forget southern Punjab, come and visit the unlikely Karachi town of Baldia for a surprising lesson on this front or, even the peaceful city of Sahiwal in north of Punjab for that matter.

Those who insist that the WoT has caused or even intensified brazen religious oppression in educational institutions, press clubs, printing presses, the judiciary and bar associations, have never visited a jail or university in Pakistan in the last two decades. They’ve been busy watching the drones in the skies and missing the systematic success of religious piety and well-funded, organised, independent rise of religious politics on the ground – pre 9/11. They pretend that the narrative on religious extremism is simply a case of misguided ideology and lack of ‘education’.

There is also the amazing and even arrogant advice to native Pakistanis that they have not ‘engaged’ enough with religion intellectually or academically and this is the cause of misguided religious bigotry and murderous results. Such arguments emerge from the luxury of historical amnesia and long-distanced clinicians who sit in western academia oblivious of the ‘engagements’ that have marked the relationship between Islamist groups, the state and civil society in Pakistan for 60 odd years.

This is unforgivable in a generation that has open access to the Munir Commission kind of reports – as just one example. Neither have they counted the plethora of Islamic universities, courses, programmes, piety lesson groups, theocratic ‘houses’, publications, textbooks and virtual discussion groups that crowd the private and public sector, apart from the madressahs. There is no secular academic engagement anymore – just the religious kind.

The drone debate has also intensified not just because its long-time protestor Imran Khan and his party now govern the targeted province but, interestingly, primarily because of the Amnesty International report. Earlier academic reports did not have the same impact. Ironically, human rights organisations such as westoxified and imperialist Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch used to be vilified for their ‘anti-Muslim’ exposure of child labour, women’s human rights abuses, terrorist atrocities and the exploitation and abuse by the Okara military farm administration against peasants. Now, by volte face, the report on drones is selectively quoted widely as objective proof of the ‘real’ oppression in Pakistan.

The content in the recent docu-film Wounds of Waziristan has been received in Pakistan with a bit of a yawn. This is not necessarily only because of the limited framing of a conflict that Pakistanis don’t need to be educated on but because it was a bad documentary. As Akbar Zaidi points out, in its attempt to focus on the human cost of war, the ineffectiveness of this documentary is mainly because it attempts to play on the guilt of American audiences (hence the repeated equation of New Jersey to Waziristan???) without any mention of why the drones are there.

This decontextualised perspective is misleading too for an ignorant American audience, since the film gives the singular impression that this is a war between drones and all Pakhtuns and the latter are only victims of one aggressor – the USA.

What is interesting is that some ‘anti-imperialist’ defenders of this documentary that Zaidi has clearly cut to the quick would agree to criticism of other one-dimensional productions including those produced by liberal sympathisers.

Therefore, the banned play by the progressive Ajoka group, Burqavaganza, which was a clichéd and limited production around the veil, was criticised by many of the same intellectuals who demanded more nuance and depth in political content in cultural productions. Such critics (including myself) were all too ready to dismiss the false binaries and stereotypes and decontextualised portrayal of the burqa and Islamists in the play.

For all their insistence that the WoT is a product of American hegemony and Pakistan complicity of the 1980s, and that we must be aware of the context, context, context, suddenly, all that is thrown out of the window when it comes to drones. Somehow, it’s perfectly alright to suspend the effective and real agenda of the militants and pretend that the wounds of Waziristan are only inflicted by one aerial side.

Also interesting is the argument that calls for accountability of the illegality of drone warfare. Not once, in either the documentary nor in the writings of these anti-imperialists nor in Imran Khan’s rhetoric is there a demand for accountability of the Pakistani defence services. This is not connected nor discussed in the context of the fact that an operation took place in Abbottabad after which there was zero accountability or consequences.

All such efforts support the myth that there is this invisible entity that falls between the military and government that permits the WoT to continue. This makes it simple to erase Pakistan and pretend that this is an ongoing colonial war against Waziristan. Wounds of Waziristan type of narratives aid such airy false analysis.

Such limited approaches, as exemplified in the new narrative that focuses exclusively on drones and America, are unlikely to end the conflict – at the very least, they won’t lead to staying peace.

The writer is a sociologist based in Karachi. Email: afiyazia@yahoo.com

-

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

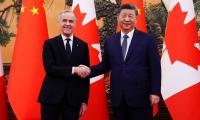

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training -

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light

Wyatt Russell's Surprising Relationship With Kurt Russell Comes To Light -

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push

Elon Musk’s XAI Co-founder Toby Pohlen Steps Down After Three Years Amid IPO Push -

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down

Is Human Mission To Mars Possible In 10 Years? Jared Isaacman Breaks It Down -

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career

‘Stranger Things’ Star Gaten Matarazzo Reveals How Cleidocranial Dysplasia Affected His Career -

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer

Google, OpenAI Employees Call For Military AI Restrictions As Anthropic Rejects Pentagon Offer -

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis

Peter Frampton Details 'life-changing- Battle With Inclusion Body Myositis -

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI

Waymo And Tesla Cars Rely On Remote Human Operators, Not Just AI -

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds

AI And Nuclear War: 95 Percent Of Simulated Scenarios End In Escalation, Study Finds -

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years

David Hockney’s First English Landscape Painting Heads To Sotheby’s Auction; First Sale In Nearly 30 Years -

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

How Does Sia Manage 'invisible Pain' From Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome