A way out in Kashmir

In 1998, the foreign secretaries of India and Pakistan met to set in motion the ‘Comprehensive Dialogue’ process as a part of the bilateral approach to resolve lingering disputes including Kashmir, which – in hindsight – was relegated to the level of issues such as Siachen and Sir Creek. This also indicated Pakistan’s readiness to seek negotiated settlement of the issue which could have ventured beyond the route stipulated in the UNSC Resolutions. A ‘third option’ was being whispered beyond the precincts of governmental talks but hadn’t yet begun to be as readily acknowledged within the circles of both governments.

Pakistan was far more ready to search for creative solutions. This got enunciated in backchannel discussions between formally appointed interlocutors, and the more informal but equally influential Track II dialogues over time. It also established, again over time, Pakistan’s willingness to look beyond the stringent domains of the UNSC prescriptions.

The Chenab Formula since the early 1960s had toyed with the thought of dividing J&K along River Chenab, granting all areas north and west of the river to Pakistan and the three districts south and east of the river to India. If anything, it showed Pakistan ready to compromise. Half of Jammu, all of the valley and Ladakh by this arrangement were to be granted to Pakistan while the three southern districts in Jammu – which constituted twenty percent of the total disputed area of Kashmir would go to India. Obviously there were no takers of the proposal in India. But, importantly, Pakistan seemed ready to play footsie. On Kashmir, please note.

Musharraf created his own concoction which came to be known as the four-point formula aimed at eventual demilitarization of Kashmir through a graduated process, first making the LoC irrelevant over time and enabling free movement of people and trade between both sides of Kashmir. The latter two were put in place right away and are ongoing measures put on hold frequently by the increasing feuds between the two militaries. Even as the final shape of the resolution to the Kashmir conflict remained to be considered in time, here was Pakistan dealing differently in the process from the strict regimen of a plebiscite prescribed by the UNSC.

While the backchannel contacts of quiet diplomacy between the two nations have persevered even in the worst of conditions, possibly ensuring peace through desisting from overly aggressive and impulsive measures, the Track IIs went even farther than most in innovation, bordering at times on cooperative mechanisms and joint protectorate over Kashmir. Such variations in consideration and the flexibility to walk away from the zero-sum mindset was instructive. The military-civil bureaucracy and the civil-society-academia leaderships in both countries were willing to look at more innovations – away from the hardened structures of the United Nations Resolutions. Was Pakistan weakening in its resolve to ‘win’ Kashmir? This was the right wing’s frequent refrain in Pakistan.

Kargil and the December 13 attack on the Indian parliament on the one hand disrupted the process while on the other added impetus to regain direction after the necessary healing period was over. General Musharraf who was demonized in India for Kargil became their favourite poster boy in later years for his more malleable approach. It took a while for India to accept his overtures but then they took such fancy to him that they regret not proceeding fast enough to resolve Kashmir through his four-point proposal.

In every such period of tension or near-war, the first recourse of Pakistan was to reiterate adherence to the UNSC resolutions to spite India. Which literally meant that if and when the two sides were talking, Pakistan by interpretation had moved away from its position of rigidity on the UNSC resolutions but as soon as the talks discontinued Pakistan’s position ratcheted back up to the zero-sum option from 1948.

India surely wasn’t blind to such variations and progressive dilution of Pakistan’s stance which aimed to proffer peace over war. If the world at large saw this as an interplay of two neighbouring countries into convenient accosting with cycles of jaded distancing, that is what they saw.

The Kashmiris in the meanwhile continued to suffer. In Pakistan it was popular to suggest that waiting out for a solution to present itself over time was always the right course than reading the situation around stagnation and a perpetual bind of animosity which had straitjacketed minds in both countries. Pakistan would be the loser in the long run since it had more to cover in terms of developing its people and the state.

Regardless of the authenticity of the allegation, Mumbai 2008 gave India the opportunity to tighten the screws around Pakistan. Pakistan found itself on the defensive despite the moral and legal strength of its argument on Kashmir. That is also when India sensed the moment. Congress used it as a convenient subterfuge and reveled in seeing Pakistan cornered. The BJP under Modi employed it as a deliberate strategy to malign, label and isolate Pakistan to the fringes of irrelevance. Gradually, India held controls to calibrate the level of intensity between the two sides.

Modi may have surreptitiously manipulated the control of Occupied Kashmir but he has truly turned the tables on Pakistan using his two-thirds majority to great – even if shameful – effect. As an extension to his much-touted defensive-offence it now cavorts Azad Kashmir. In so doing it intends to narrow Pakistan’s strategic choices while putting its own luck to test. There remain, however, far greater stakes for Pakistan in this game of chickens.

Pakistan stands on the verge of a strategic fork. If it must win IOK back, it shall have to fight to win it. India isn’t giving it up through moralizing. This will need a new and an appropriate strategy. The international system is unlikely to make it available on a plate to Pakistan. A zero-sum paradigm will also entail its own cost. A subsidiary option is to bide time and await the reaction in Kashmir to build on it. That will perpetuate strife.

The second course is to seek virtue in vice. Place the Kashmiri front and center and win him some respite from Indian suppression. That is where some international partners may come handy. Pakistan’s wider role in fostering stability within and without will help it gain credibility and its rightful weight in global and regional matters. It must build up on its portfolio for peace in Afghanistan and assist in lowering tensions in the Gulf.

If the US and the world at large wish to assign India a role in regional affairs, proportionate to its geographical and economic size, Pakistan must shed its inhibitions to coexist with other players. However, that must come with the condition of India shedding its demonic ways in destabilizing South Asia and the entire region.

India’s international allies will have to play their part; otherwise, war remains an expedient resort for lack of necessary empathy. In which case humanity will have failed, not just South Asia.

Email: shhzdchdhry@yahoo.com

-

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss -

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning -

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding -

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene -

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce -

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All'

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All' -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals -

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked -

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

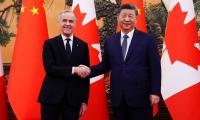

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training